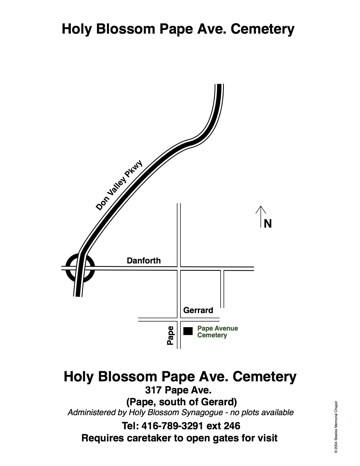

Cemetery Description

Pape Avenue Cemetery, officially known as Holy Blossom Cemetery, is the first Jewish cemetery in the city of Toronto, Canada. The small cemetery is now closed to new burials, and is mostly hidden within the residential neighborhood of Leslieville.

It was established in 1849 by two prominent local businessmen Judah G. Joseph and Abraham Nordheimer. At the time the nearest Jewish cemeteries were in Montreal or Buffalo, and Joseph was concerned for his fatally ill son Samuel, who eventually became the first burial in the new cemetery. The location near the corner of Pape (then called Centre Road) and Gerrard was then in still rural areas to the east of the city. It was not close to much of the Jewish community, but was a convenient location to purchase.

It was one of the first Jewish institutions established in Toronto, being opened some years before the city’s first synagogue. When Toronto Hebrew Congregation, the predecessor to Holy Blossom Temple, was established in 1856, it took over management of the cemetery, and continues to run it today. Over the next decades almost all the early founders of Toronto’s Jewish community would be buried there. In 1883 the nearby Jones Avenue Cemetery opened, serving the members of Beth Tzedec Congregation’s two predecessor synagogues. The small Pape Avenue Cemetery quickly ran out of room, and it was closed to new burials in the 1930s. To replace it, Holy Blossom opened a new cemetery further east on Brimley Road in Scarborough, Ontario.

Jewish Customs at Cemeteries

Basic respect should be shown. Refrain from eating, shouting, singing.

Try to avoid walking on the graves if possible.

Learn More

A visit may evoke words of Psalms or the El Maleh Rahamim memorial prayer.

Sephardic liturgy’s Hashkaba prayer is said in hope of a peaceful

rest for the departed. Syrian Jews read the lines of long acrostic Psalm

119 that spell out the Hebrew name of the deceased. This psalm expresses

loyalty to the word of God and hope for salvation. The words that come to

mind are also prayers if only written in the prayer book of the heart.

With minor exception you can visit a cemetery or grave on virtually all weekdays.

Visitation are customarily not made on chol ha’moed–the middle days

of Passover and Succot–nor on Purim, as these are holy days of joy. While

visitation of the grave is permitted at almost any time, excessive visits are

discouraged. “The rabbis were apprehensive that frequent visiting to the cemetery

might become a pattern of living thus preventing the bereaved from placing

their dead in proper perspective” (The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning,

Maurice Lamm, p. 192).

Because contact with a dead body is considered a defilement, Kohens are

not allowed into a cemetery except in the case of a very close relative,

because they would then be unclean and unable to perform their priestly

function. For the rest of us, the mitzvah (blessing) of performing these

services for a departed person outweigh the defilement of being made unclean.

Transitions in Jewish life are often accompanied by water. A body is

bathed in a poignant, dignified ceremony before burial. Jews-by-choice mark

their entry into the Jewish people by immersing themselves in mikveh waters.

Similarly, hands are washed after a cemetery visit to mark the departure

from the surroundings of death to an attachment with life. Many of the

cemeteries in the Toronto area have hand washing stations, many of which

have been built by Steeles Memorial Chapel

When visiting Jewish graves the custom is to place a small stone on the

grave using the left hand. This shows that someone visited the gravesite,

and is also a way of participating in the mitzvah of burial.

Leaving flowers is not a traditional Jewish practice.